Are you allergic to cats? John Hopkins Asthma & Allergy Center is looking for people interested in participating in a study of new treatment for cat allergies. Earn $425, if accepted.

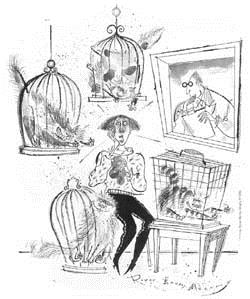

Not long after I’d spotted this ad in the morning newspaper, I was sitting in a cinder-block room in the basement of a Baltimore research lab with a meter strapped to my shoulder and a tube wrapped around my neck to measure the allergens I was breathing. Two large, pampered felines stretched languorously in a cage near my feet, their fur and dander drifting placidly in the unmoving air.

A physician was in attendance in case I suffered some sort of traumatic reaction, like not breathing, and a masked research assistant sat watching me closely, her clipboard and pen at the ready.

“Just breathe normally, ” the research assistant said ominously, “We’ll see how long you last.”

Cats and I have a long, unhappy history. Put me in a room with one, and I am soon reduced from a well educated, poised professional woman to a sneezing, scratching, puffy-eyed hag. This has not endeared me to my in-laws, all of whom are cat lovers with at least one – and the case of my brother-in-law, five – of the critters.

As I enter their domain, cats abandon their reputed aloofness, choosing instead to greet me by enthusiastically rubbing against my legs, pouncing onto my lap or curling up on my pillow. Others might think this is an endearing sign of affection, I know better. Cats have a sadistic sense of humor. Just as they enjoy torturing small rodents and bugs, so they delight in causing discomfort in any member of the human race they perceive as vulnerable. I’m prime prey in their slitted eyes. Maybe this experiment could be my salvation, outwitting the cats and endearing me to my in-laws.

The $425 didn’t sound too bad, either. OK, so it wouldn’t be a financial windfall. But, if the vaccine worked, at least I wouldn’t have to sleep in a hammock outside when I visited my mother-in-law. Besides, I told myself, I was doing something good for humanity.

So I made my first visit to the lab. The counters were filled with racks of test tubes, small vials of unnamed solutions and binders for recording results of tests and interviews. I was in one of those binders, known for the purposes of science as No. 266 of the Allervax Cat Allergy Vaccine Protocol.

My noble intentions began to evaporate as they prepared the first stage of testing. The lab technician would inject me with several small doses of cat cocktails (believe me, you don’t want to know what was in them) to see what sort of reaction I’d have. The allergens would cause a welt, and the size of the welt would indicate just how allergic I was. The welts would itch, I was told, but I couldn’t scratch them.

Within seconds, I proved I was a prime candidate. Intriguing splotches began to rise on my arm, like some sort of special effect in a bad science fiction movie.

“Oooh,” crooned the lab tech, pointing to a welt that resembled a new Eastern European republic. “That’s a nice one.” She used a felt-tip marker to outline each splotch, then slapped a strip of tape over the mark and transferred it to my page in the binders – a sort of medical version of using Silly Putty to transfer the Sunday comics.

The “Cat Room Challenge” came a few days later. The idea was to see what reaction I had when I was in close contact with cats.

The first step was testing my lung capacity. I was to empty my lungs of air as rapidly and forcefully as possible. I blew hard into a metered tube, while the assistant cheered me on. “Harder! Push harder!” she urged, sounding for all the world like a Lamaze coach in a delivery room.

Satisfied, she left to get the Cat Room ready. Two well-tended felines had the run of the unventilated room. There were cat toys scattered about the floor and a cot for the cats to lie on. The sheets on the cot had been there a long time. They were saturated with dander, cat oils and fur. The assistant closed the door and shook out the sheets so that the room reeked of Essence of Feline.

You don’t have asthma, do you?” asked the doctor who was on standby. I assured him I did not. “Oh, good,” he said, looking relieved.” “It can get pretty exciting when someone has an asthma attack.”They then wired me up with a meter that would measure how much cat “stuff” I inhaled and correlate that with my reactions. Both of them assured me there was no mandatory time that I had to stay in the room with the cats. The longest the test ran was 30 minutes, but I could call it off whenever I wanted.

They call it a challenge, right? Send me in, coach! I was good to go for the entire half hour.

Just before we entered the room, the research assistant put on a breathing mask. I asked why.

“Oh,” she said with a shrug, “I’m allergic to cats,”

Say what?

Another shrug. “It’s a good job,” she replied.

We settled in. I held a list of a smorgasbord of symptoms – sneezing, itchy and watery eyes, runny nose, tightness in the chest, and difficulty in breathing – with a rating of “not noticeable” to “annoying.”

It didn’t take long for the symptoms to start. I sneezed. The research assistant made a tick on her chart. I sneezed again. Another tick. Again. And again. By the time I finished, I had set a new record: 48 consecutive sneezes in a five-minute period. The research assistant was impressed. The cats looked bored.

After 15 minutes, we left the room and tested my lung capacity again. then we went back in for the last half of the challenge. As we came back in, the cats were sprawled on their backs, stretching with the indolent pleasure only cats can show. I was sure they’d been laughing the entire time I’d been gone.I didn’t sneeze much this time, but I could feel my chest tightening. When I answered the assistant’s questions about my symptoms, I discovered I had developed a certain huskiness of voice reminiscent of Lauren Bacall. Quite appealing, actually.

Finally, the half hour was up. I had my lung capacity checked once more. It seemed little affected for all the trauma.

“Not bad,” the doctor said.

I smirked as I passed the Cat Room door, feeling victorious. The cats cheerfully sprang from their cage to resettle themselves on the cot and await their next victim.

Yet for me another test was on the agenda. The panel on the door read: “Nasal Provocation Lab.” I held a small blue plastic tray under my nose while doses of cat dander were misted up my sinuses. I was to let any “nasal discharge” run into the tray. If I sneezed, I was to sneeze into the tray as well.

There were three “spritz and sniff” tests that day, with a higher concentration of cat “stuff” in the solution each time. At the end of each test, the tech took the tray and funneled the contents into test tubes. This was not the sort of thing you imagined when you decided on a career in health care, I thought. I wondered what the tech put on her IRS forms as a job title. Nasal Discharge Analyst?

I also wondered why the Johns Hopkins Asthma & Allergy Center purchases its facial tissues from the bottom end of the consumer market. By the end of the day, my upper lip was raw. Some of that $425 would go to buy softer tissues for future tests, I decided.

Finally, it was time for the vaccine. After all of the experiments and testing, it was anticlimactic. From what I could tell, there was no improvement in my reaction to the cats at the Asthma & Allergy Center, or at my mother-in-law’s, for that matter. Still, it was fun to be on the cutting edge of scientific research. I wouldn’t mind doing it again, I thought, as I left the lab for the last time. I even petted the cats goodbye. I left a box of soft tissues on the counter at the Nasal Provocation Lab, collected my final paycheck, cashed it and treated myself to lunch.

Reading the day’s newspaper over my hamburger, I spotted a small ad on the back page:

Do you suffer from autumn

ragweed? Looking for people to

participate in a 14-week study

of ragweed allergies. Earn

$400-$700 if accepted….

Writer Fran Severn lives in northern Maryland with three dogs — who shed but don’t make her sneeze.